We’ve spent the better part of the past century sterilizing everything in sight, from milk to meat to produce, our hands, and anything else that might carry a germ or two. Our germ awareness became especially heightened during the last two years of the global coronavirus pandemic.

Some call it “germophobia,” and I confess I’m the biggest germophobe in sight. I wash my hands frequently, scrub raw produce clean and sometimes soak it in white vinegar or other natural microbe-killers and keep an immaculate house (no outdoor shoes allowed).

I go crazy with caution in public restrooms (my hand seldom touches anything in a public restroom except water and a paper towel).

Now it turns out all this caution may be a mistake. Research is turning up plenty of evidence we may have shot ourselves in the foot with all this cleanliness. Germs can be good for you.

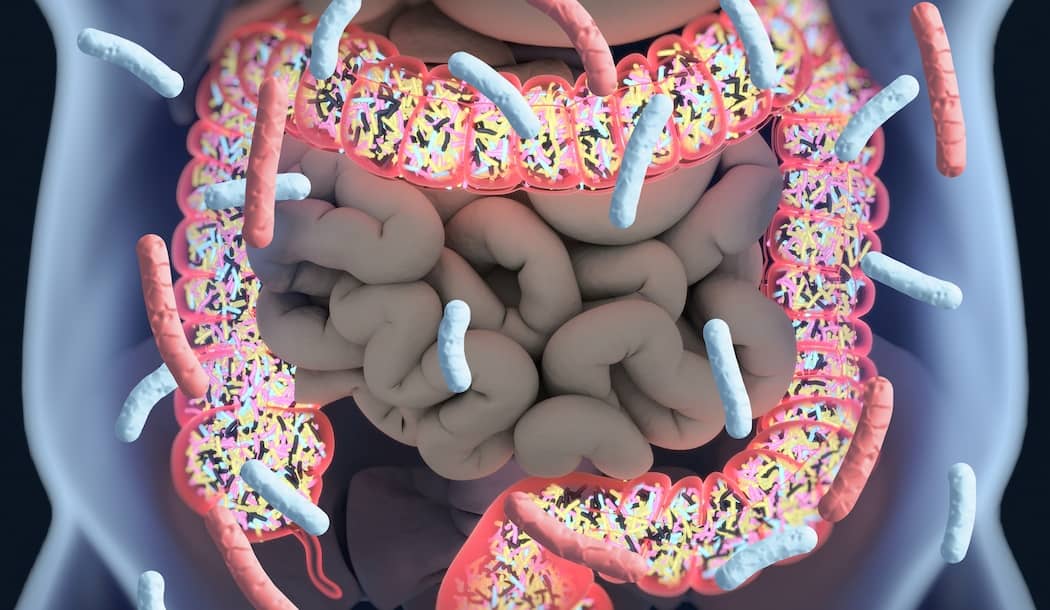

You’re not alone in your body. Scientists report that you share it with about 100 trillion microbes. They’re on the surface of your skin, on your tongue, and deep in the coils of your intestines. And you should be happy they’re there.

The microbes outnumber you by ten to one

The hundreds of bacterial species that call you home completely outnumber your own cells. For every intrinsically human cell in your body (i.e., one with your DNA), you have ten resident microbes. And it may surprise you to discover that very few of them cause a disease.

The quality of your health, as researchers have been learning over the last two decades, is intimately linked to your microbial health. You probably know about “good” bacteria in your intestines. But that’s old stuff. Other organisms play a much greater role in our health than mere digestion.

Your second genome

Your gut constitutes what’s known as your “second genome”. The first one is your own DNA, your 23 chromosomes present in every cell that you would normally think of as “yours.”

But the second genome may exert a far greater influence on your health than the genes you inherited from your parents. An astounding 99 percent of your genetic expression is microbial. You’re stuck with the genes you got from your parents, but you may be able to radically reshape your second genome.

And you should want to, because disorders in your gut can lead to a whole list of chronic diseases, infections, allergies, and obesity.

Scientists are still unfolding this mystery

Nutritionists were at one time confounded about why a group of complex carbohydrates called oligosaccharides are found in breast milk, since babies lack the enzymes to digest them. Turns out they aren’t there to nourish the baby itself, but a bacterium in the baby’s gut called Bifidobacterium infantis. This friendly bacterium helps break down the oligosaccharides in the milk.

Mother’s milk isn’t sterile… it provides both a “prebiotic” (a food for microbes) and a “probiotic” (actual beneficial microbes). When nature creates a food, it feeds both the person and the gut bugs. Try doing that with processed foods!

And there have been many more seemingly unusual discoveries. For example:

- Obese mice transplanted with the intestinal microbes of lean mice lose weight, and vice versa. The reasons are still unknown.

- Gut bacteria of a lean donor were transferred to males with metabolic syndrome, resulting in marked improvements in insulin sensitivity.

- Installing a healthy person’s gut microbes into a sick person’s gut has been effectively used to treat the antibiotic-resistant intestinal pathogen C. difficile, which kills 14,000 Americans annually.

What does any of this have to do with cancer? Plenty…

A hidden cause of inflammation

Inflammation is linked to nearly every chronic disease. It’s a common feature of metabolic syndrome, which predisposes people to cardiovascular disease, obesity, Type 2 diabetes, and even cancer.

But is inflammation a symptom or the cause?

The new theory is that inflammation, and thus many cancers, might begin with out-of-whack microbes in your gut.

An internal skin called your epithelium lines your digestive tract. It is literally large enough to cover a tennis court. More than 50 tons of food passes through it during a lifetime.

Your beneficial bacteria play a crucial role in maintaining the epithelium’s health. Your epithelium doesn’t get its nourishment from your bloodstream as other tissues do. Instead, it’s nourished through bacteria, especially bifidobacteria and Lactobacillus plantarum (common in fermented vegetables).

A malnourished epithelial barrier becomes permeable, allowing toxic byproducts of bacteria and proteins to leak into your bloodstream, initiating an immune system response.

Eventually, this low-grade internal inflammation leads to metabolic syndrome and the chronic diseases linked to it.

An experiment conducted in Brussels is telling…

Mice fed a junk food diet also developed compromised gut barriers and endotoxin leakage, leading to metabolic syndrome. The researchers concluded that, at least in mice, gut bacteria can INITIATE the inflammatory processes linked to obesity, insulin resistance and some cancers by increasing gut permeability… suggesting that these ailments may begin with the gut.

Love ’em or lose ’em

If you don’t love your gut bacteria, they can’t help you.

Microbiologists studying the human gut are reluctant to make eating recommendations, citing the need for more study. But when asked what measures they took to improve their own health based on what they’d learned, most admitted to these:

- They now avoid taking antibiotics, which kill healthy microbes as well as damaging ones, whenever possible.

- Some spoke of relaxing the sanitary regime in their homes, and encouraging their children to play outside in the dirt and with animals.

- Many said they’d eliminated or cut back on processed foods, out of concern for additives, antibiotics, and lack of fiber.

- They choose foods likely to encourage the growth of good bacteria… like fermented foods.

- They eat a wider variety of raw plant foods, as different microbes enjoy chomping on different plant fibers. It’s one of your best bets for increasing your microbial diversity.

Infectious disease

The coronavirus pandemic has changed the playing field for infectious disease. Up until recently we haven’t worried for decades about deadly outbreaks, but historically, infectious disease has always been a problem. At one time, TB was the leading cause of death!

In my own family, my grandmother died of an infection acquired in giving birth to my mother — most likely because the doctor didn’t wash his hands. And my grandmother’s brother had died just a couple years before that from typhus, most likely acquired from fecal-contaminated drinking water. So, my great-grandparents lost both of their children in their twenties, and my mother never knew her mother — all because people didn’t worry about germs.

I’m not nostalgic for the old days. Modern medicine’s great claim to fame is the victory over these diseases and others caused by germs and viruses like the coronavirus. But oddly enough, if you live past the age of 50 or so you’re probably not as healthy as a person who lived to that age in 1900. Fewer people DID live that long, but those who did were remarkably hardy.

Is all the chronic disease surrounding us linked to unintended side effects of our war on pathogens (i.e. germs)?

For example, rural people from West Africa and the Amerindians in Venezuela not only have a larger selection of microbes than we have — they have different actual microbes than Americans and Europeans. They tend to live closer to the earth, in a dirtier environment, and eat more plant foods. And they have far less chronic disease.

My takeaway

So don’t wait for any “official” recommendations to improve your gut health. The components of a gut-friendly diet are already in your farmer’s market and your grocer’s produce and fermented foods aisles.

You depend on microbes for your life and health, so it’s in your best interest to align yourself with their best interests by feeding them the things they like to eat.

And don’t look for absolute germ control. It’s likely we’ve gone too far in our zeal to kill absolutely all bacteria. It’s probably impossible to have absolute control without collateral damage.

Antibacterial soaps, for example, are overkill. Regular soaps are adequate.

All this said, I’m still going to avoid touching anything in public restrooms.

Best regards,

Lee Euler,

Publisher