Vaccines have been a hot topic as we make our way through the coronavirus pandemic. But not all vaccines target viruses and the like. There’s also a vaccine for cancer. Best of all, it doesn’t employ drugs, just your own immune system.

It’s called Dendritic Cell Therapy, or DC therapy, though most people refer to it as the Dendritic Cell vaccine.

In a nutshell, it’s an approach to cancer treatment that uses your body’s own immune system to fight cancer. There have even been some reports of complete turnarounds, including in some late-stage cancer patients — essentially hopeless cases — who didn’t respond to other therapies.

But that’s not all.

Not only is DC therapy a promising treatment for advanced cancer, it’s also showing promise as a tool to prevent cancer in the first place.

Dendritic cells: What they are and what they do

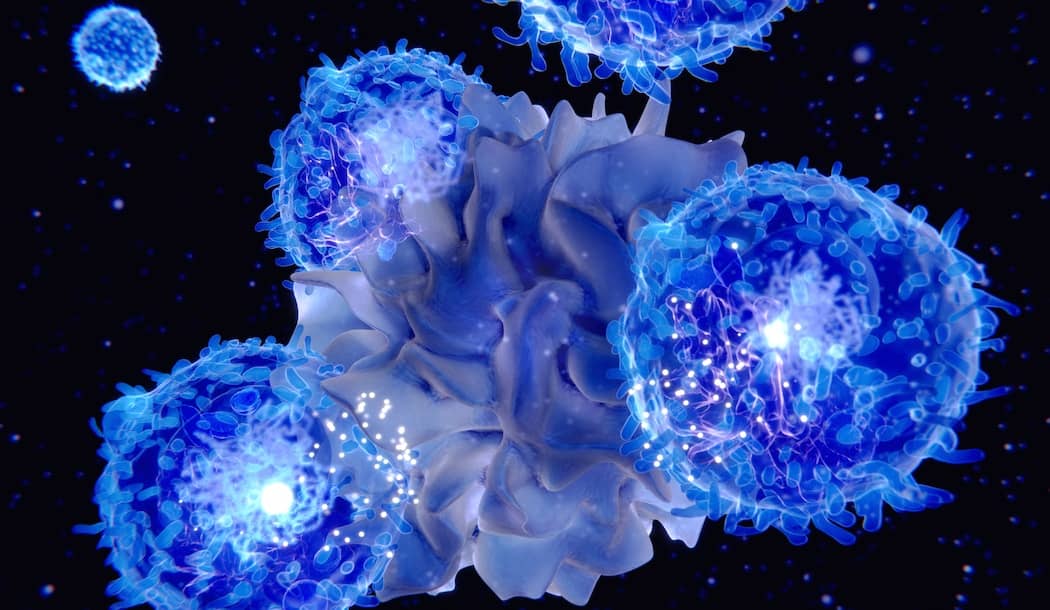

Dendritic cells are a type of immune cell found in mammals. Their role is to recognize and attack foreign invaders. They function as a messenger cell or information carrier that helps activate a type of immune system cell called T-cells, giving the T-cells the capacity to be aware of threats to the body. Once alerted to danger, the killer T-cells circulate throughout the body to destroy the foreign invaders.

Dendritic cells are present in the skin and other tissues that have contact with the external environment, such as the lining of the nose, lungs, and stomach. They exist in an immature state in the blood. But although they’re extremely powerful, dendritic cells don’t occur in big numbers in the body. At any rate, there aren’t enough of them to prompt a significant immune response to cancer.

Dendritic Cell Therapy changes that. It boosts the number of dendritic cells in the body so there are more messengers to activate killer T-cells to attack invading cancer cells.

“Most wanted” posters for the immune system

Cancer treatment vaccines are designed to activate B-cells and killer T-cells. They alert those cells to the foreign invader (cancer). Vaccines, which are usually administered by injection, do this by introducing antigens into your body.

An antigen is an agent that provokes an immune system response. It’s basically something that “isn’t you” and may be harmful. An antigen may be a protein, or some other type of molecule found either inside or on the surface of a cell.

Dendritic cells are antigen-presenting cells. They basically serve as messengers between the innate immune system (your body’s first line of defense) and the adaptive immune system, which remembers pathogens (i.e. germs) that it has seen before, and mounts ever stronger attacks against them.

This part of the immune system is called “adaptive” because it’s the body’s system for preparing for future challenges, not merely for the antigens it’s seeing now.

Imagine your home is invaded by a burglar, but you’re able to scare him off. Then you buy a security system for your home, so you’re better prepared the next time than you were the first time. That’s an adaptive response.

Your immune system likewise learns from its encounters with invaders and prepares for the next round. It does this by “remembering” how to tell an invader from a harmless cell. That way it can pick the invader out in a crowd and head right for it.

What’s the role of dendritic cells in all this? One researcher compared dendritic cells to “most wanted” posters for the immune system, since they tell the killer T-cells exactly which antigens to go after.

Think again of the invader of your home. Imagine you were able to get his picture. Or maybe you already had a security system that captured his image on video. You circulate his picture to the neighbors, so next time he’s seen in the neighborhood, he’s reported immediately. He never even gets near your house.

Now that’s a really adaptive response!

A glimpse into how the vaccine works

To make the dendritic cell vaccine, researchers take a patient’s dendritic cells and expose them to immune cell stimulants. This prompts dendritic cell development. After that, the dendritic cells are exposed to antigens from the patient’s cancer cells. Think of this as showing all your neighbors a picture of the criminal, so they’ll know him if they see him.

Then, the combination of dendritic cells and antigens is injected back into the patient. From there, the dendritic cells work to program the T-cells, so they know exactly what to attack.

So far, this approach seems to work well for most patients, except those with depressed immune systems. Unfortunately, chemotherapy and radiation depress the immune system.

The Dendritic Cell Therapy may also be inappropriate for patients who are pregnant, who suffer from active autoimmune disease (such as rheumatoid arthritis), or who have recently received a blood transfusion.

This works on a growing list of cancers…

This treatment has some of the biggest players in conventional medicine nodding their heads.

For example, the former Vice President of Research at the American Medical Association, Dr. Harmon Eyre, once said of Dendritic Cell Therapy, “Patients’ responses are far out of proportion to anything that any current therapy could do.”

Researchers feel immunotherapy with dendritic cells shows a lot of promise even for some of the toughest cancers, such as advanced prostate cancer. Several trials have shown promise in extending survival for prostate cancer patients.

Melanoma and kidney cancer appear to respond best, but the vaccine has also shown documented benefit in B-cell lymphoma, myeloma, colon cancer, ovarian cancer, breast cancer, and renal cell cancer, among others.

There have been more than 20 trials examining the effectiveness of Dendritic Cell Therapy on everything from ovarian and lung cancer to Stage IV Melanoma. The results suggest that the best time to attempt Dendritic Cell Therapy appears to be when the disease is stable and the patient isn’t going through chemotherapy or radiation, when a patient is at risk of the disease recurring, or when all other options have been exhausted.

The future for immunotherapy is bright

Dendritic Cell Therapy is FDA approved and some experts predict that it will become commonly used as a stand-alone therapy, at least in certain patients. It’s also likely to be used in combination with drugs that target suppressor pathways in patients with metastatic cancer (i.e. cancer that has spread beyond its original location).

I think the outlook for immunotherapy is very exciting. It’s nice to know researchers are at last tapping the true power of the body’s natural immune system.

One researcher even said these vaccines could possibly lead to the complete prevention of cancer. That’s a bright future I’m looking forward to.

Best regards,

Lee Euler,

Publisher

References:

- Dendritic Cell Vaccine:https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32205087/

- “Is there a cancer vaccine?” by Kevin Bonsor, Discovery Fit & Health.http://health.howstuffworks.com/diseases-conditions/cancer/facts/cancer-vaccine2.htm

- Cancer Treatment Vaccines, National Cancer Institute Fact Sheethttps://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/types/immunotherapy/cancer-treatment-vaccines

- “Clinical Applications of Dendritic Cell Cancer Vaccines.” Joseph Baar. The Oncologist. April 1999. Vol 4, No 2. 140-144.

- “Clinical applications of dendritic cell vaccination in the treatment of cancer.” Cranmer, LD, et all. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004 Apr;53(4):275-306. Epub 2003 Nov 26.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14648069?dopt=Abstract

- “Dendritic cells and immunity against cancer.” Palucka, K., et all. Journal of Internal Medicine10.11.11/j1236http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02317.x/pdf

- “Dendritic cell vaccines for the treatment of prostate cancer.” Lehrfeld TJ, Lee DI. Urol Oncol. 2008 Nov-Dec;26(6):576-80.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18996314

- “Using Dendritic Cells to Create Cancer Vaccines.” November 13, 2007 presentation by Edgar Engleman for the Stanford School of Medicine Medcast lecture series.http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=da9z30QsE9k&feature=player_embedded